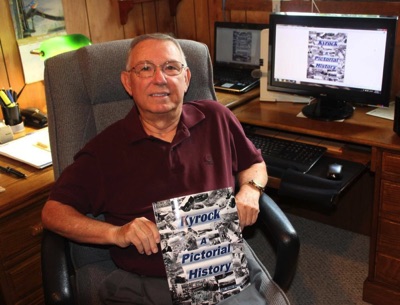

Ernie Elmore, of Paris, Ky., with his new book "Kyrock: A Pictorial History."

To a traveler passing through on the way to somewhere else, Kyrock might come across as a nondescript hamlet, but the Edmonson County community was a bustling company town for much of the first half of the 20th century.

Now, Ernie Elmore, a retired chemist and pharmaceutical quality engineer with family ties to Kyrock, has published “Kyrock: A Pictorial History,” filled with pictures of the town from its days as the hub of asphalt rock mining and processing.

Elmore, who lives in Paris in central Kentucky, grew up on a farm near the forks of the Nolin and Green rivers, and members of his family and his wife’s family worked at Kentucky Rock Asphalt Co., from which Kyrock derives its name.

In its heyday in the 1920s, the company operated eight quarries in Edmonson County from which thick deposits of rock asphalt were mined, processed and shipped via the area’s rivers to eventually be used to pave roads, often in areas that had not previously had paved roadways.

Elmore, who has been retired since 2008, said he felt it was important to have much of the community’s history represented in a single volume.

“I’m really not an author or a writer, but I wanted to capture as much of the local history as I could,” Elmore said. “I thought the Kyrock plant facility was such a vital part of the history of Edmonson County, and the older people who knew about it and worked there were all dying out. The next generation knew about it from the parents who worked there ... and the next generation (after that) have only heard stories about it, and sometimes not even that.”

Elmore compiled information for his book from as many sources as he could find, making use of pictures belonging to longtime friends and others with roots in Kyrock, as well as letters, old news articles and other sources.

Western Kentucky University’s Folklore Division had a collection of interviews done in the 1980s with former Kyrock employees that proved valuable for Elmore’s work.

“There’s so many people that only know of Kyrock as a little community now,” Elmore said. “I want to try to preserve as much of this as I could for future generations so they know what actually happened there.”

The Kentucky Rock Asphalt Co. began in 1917 through the merger of two companies involved in rock mining and paving, and new quarries and a processing mill opened at the site that would become Kyrock in 1918.

For much of the company’s tenure, Harry St. George Tucker Carmichael served as its superintendent, acting as a financial benefactor for Kyrock and helping build the community to a point when it had a population of about 2,000, along with a school, hospital, several stores and other amenities.

The company became the state’s most successful rock asphalt mining operation, staying open for 40 years and promoting itself heavily.

Elmore said he developed a great admiration for Carmichael through his research.

“To me, it was just a fascinating period in that area where they came in there and it was almost a wilderness when they got here,” Elmore said. “Mr. Carmichael was actually a genius to get this going and get everyone trained to work there. ... He brought all the supplies down the river by steamboat and kept everyone supplied there because it was just almost impassable to come by road.”

Like the rest of the economy, Kyrock was adversely affected by the Great Depression of the 1930s, with production fluctuating throughout the decade.

Carmichael developed health problems and died in 1949, around the time that more roads were being paved with petroleum-based asphalt that could more easily support heavier vehicles. Those circumstances, along with higher costs to pave with rock asphalt compared with petroleum-based asphalt, spelled the end of the company. It closed in 1957.

Elmore immersed himself deeply into the project, which became a labor of love for him. He was encouraged by his wife to continue adding to the book, which he self-published.

“There were times when I thought, ‘I don’t know if I can do this,’ but then I would get so involved in it it was almost like being there and seeing what was going on,” Elmore said.

From a 2016 Article by Justin Story in the Bowling Green News